We took it easy this morning in hopes that the weather in Florence would improve, but all of our apps said it would be a good day to get out of town, so we took the train to Pisa (I should note that the trains we took today did not run on time), arriving a little before noon.

We followed Rick Steves’ Pisa Walking Tour, beginning with a look back at the station with its Fascist-era arcade (the umbrella vendor was an omen we chose not to heed).

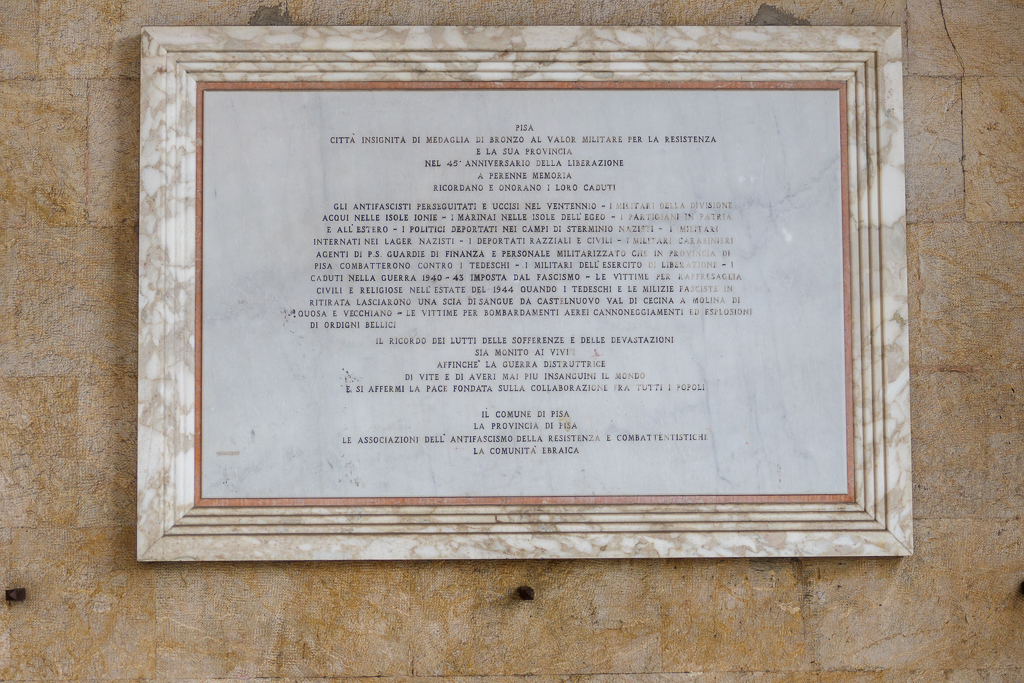

We walked to Piazza Victor Emanuelle II, which was rebuilt after WWII (Pisa was a main target and much of the city was heavily bombed, including the bridge we took over the Arno later in the day). There’s quite a lot of street art in Pisa, including a Keith Haring just off the square.

We had lunch at Leonardo Café e Ristoro and really enjoyed it – everything was fresh and delicious. We split a pistachio cheesecake, something I’d never seen in the US – I’d like to find one this good again!

We continued on Rick Steves’ route until we reached the Arno.

We added a stop at Palazzo Gambacorte (City Hall), drawn to it by the decorations on its wall.

The inside had a special exhibit commemorating 100 years of the telephone company!

We crossed the Arno on the Ponte di Mezzo, which was rebuilt after the Allies destroyed it in 1943. and continued through Piazza Garibaldi and along the high-end shopping street, Borgo Stratto, with detours to the Church of St. Michael and Piazza delle Vettovaglie, which the book calls “lively by day and sketchy by night”.

We paid our respects to Galileo (again) as well as Ulisse Dini, an Italian mathematician who attended the Schola Normale Superiore (and became its director), which is just down the street in Piazza dei Cavalieri.

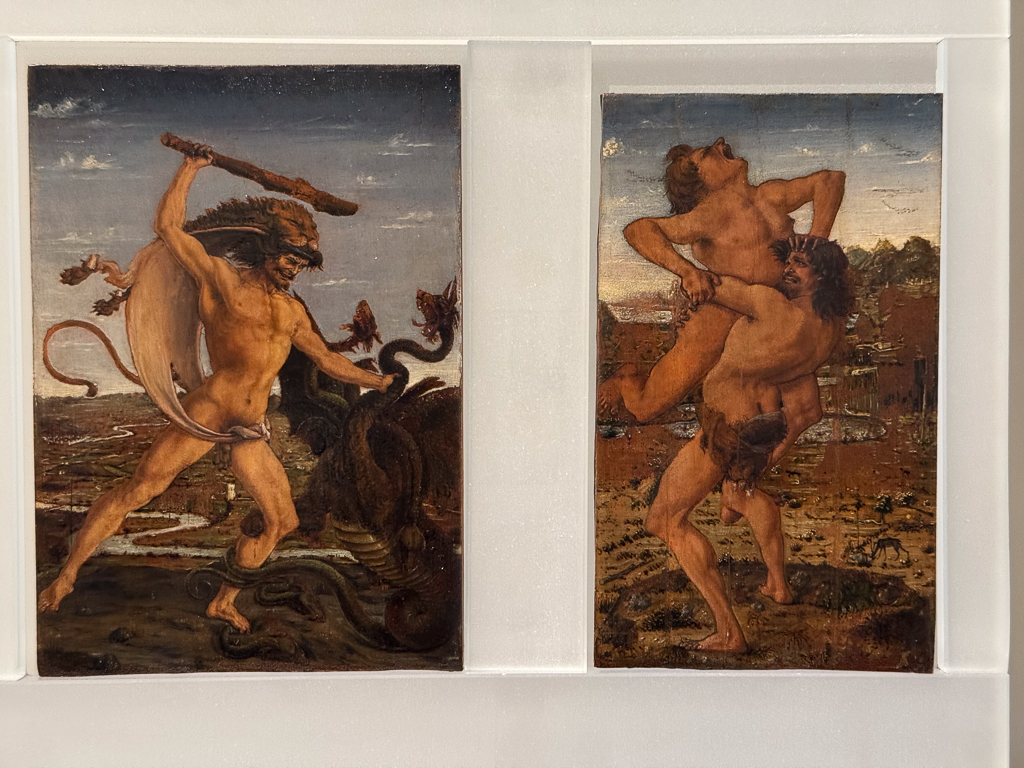

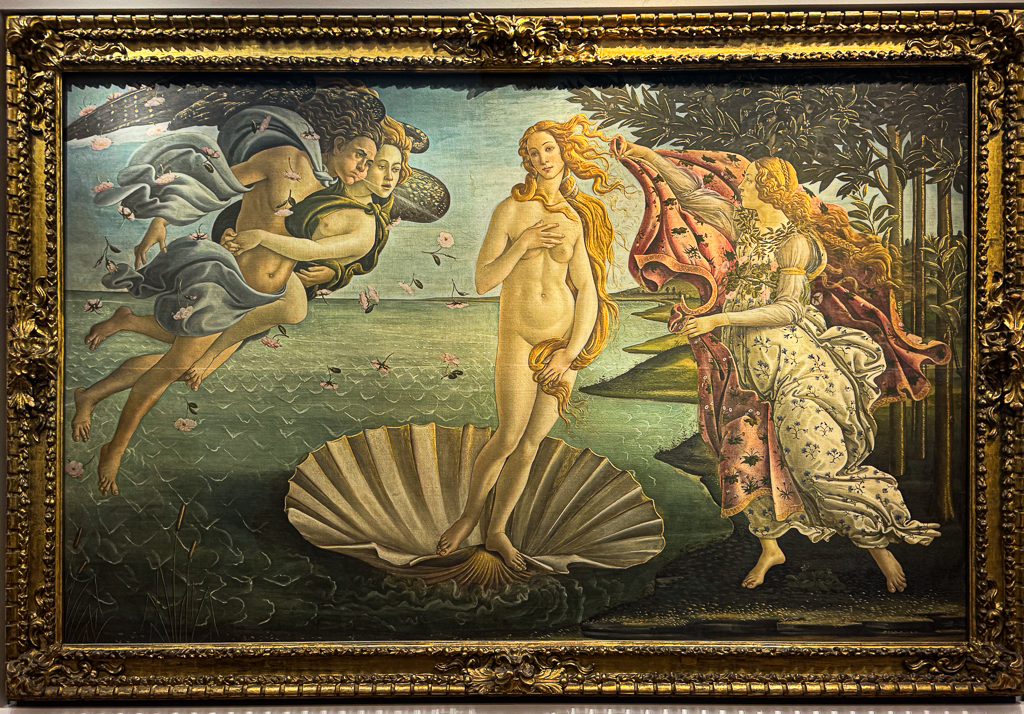

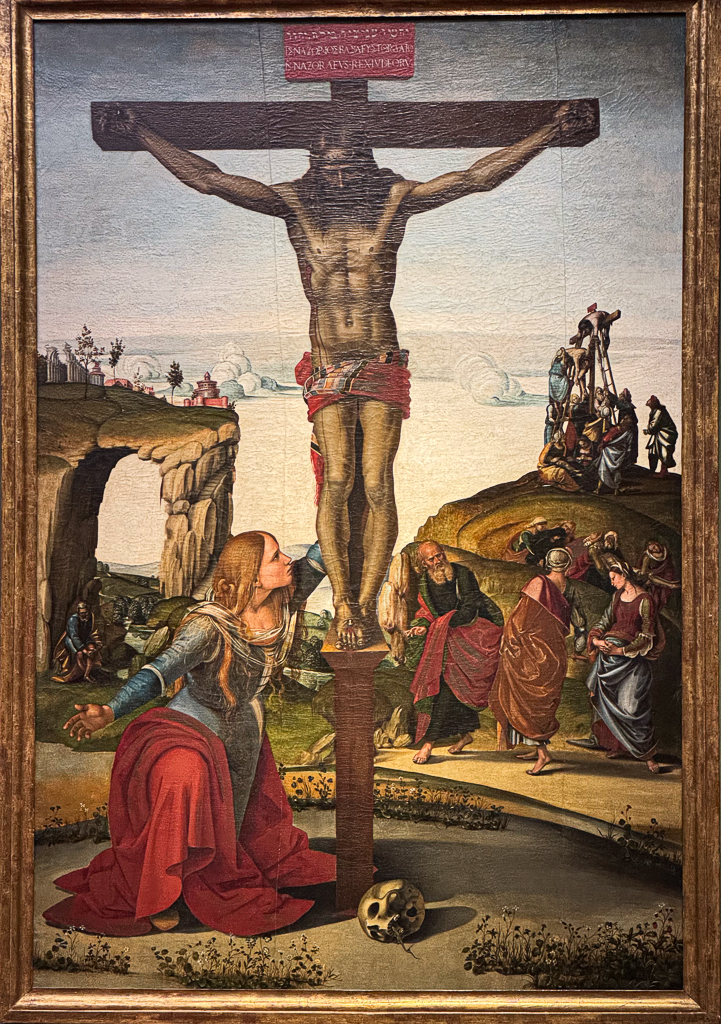

The walk ended at the “Field of Miracles” (Campo dei Miracoli), where we spent a couple of hours exploring and trying to stay out of the rain.

We left the Field of Miracles and slogged the most direct route we could find back to the train station, saying “no” to several more umbrella vendors along the way. I left my camera in the bag to keep it dry, but trust me…there was nothing interesting to photograph along the way.

As it turns out, Florence got a lot less rain than Pisa today. How do you say “c’est la vie” in Italian?